Click here to read this article in Arabic

It is doubtless that we live in a time in which we are continually surrounded and even bombarded with misinformation, fake news, and lies masquerading as truths. This phenomenon does not limit its manifestation only to politics, socio-economic issues, or education, but has also penetrated the church—the very body of Christ. Primarily, this trend continues to permeate the church not only due to the widespread ignorance that has infiltrated social media and the internet at large but also due to a lack of biblical knowledge among Christian laity and the absence of sound teaching among Bible teachers and preachers. This phenomenon is what has led me to write this article.

There is no other time in which people seek to learn more about what the Bible teaches than in a time of adversity and uncertainty. We see even those who do not believe in the Bible anxious to find out if the Bible contains any prophecies that might help them figure out what is next. Even unbelievers seek to discern the faintest thread of light in the word of God!

One of the most contentious issues of our modern day is that of the land of Israel. When it comes to the land’s history, the ethnic groups that lived in it, and its religious and political significance, views and emotions abound. Therefore, it is not my intention to make any political statement or advocate for one group’s right to the ownership of the land over the other groups. Though I have my own views on this issue, this is not what this article is about. Make no mistake, I do recognize that this article might be a cause of contention or agitation to some people. Though this is not my intention, that is to be expected. I intend, however, to lay before you simple historical facts that cannot and should not be denied or distorted. Whether these facts lead to one group’s right of ownership over the others is a different discussion for a different day. But it is not why I am writing this article.

To most people in the West the history of the ancient Near East (part of what is known today as the Middle East) is not something that is readily taught in schools or universities (unless of course in a time of crisis). Conspicuously absent is the role of the church in disseminating true knowledge when it comes to issues like this, especially as it has become a “political” issue! This leaves most non-specialized knowledge seekers in the West captive to erroneous information and altered history that has been “tailored” to fit certain agendas.

In this article I seek to shine the light of true biblical knowledge to help discern truths from lies. With uncertainty gripping the world at large and especially with the violence arising from the ancient Near East region (known to us today as the Middle East) this article seeks to answer this pivotal question: Are today’s Palestinians the descendants of the biblical Philistines? If not, who were the Philistines of the Old Testament and who are the Palestinians of our modern day? To answer these questions and more, we embark on this brief journey.

To trace the history and the identity of the Philistines, we will first begin by exploring their mention in the Bible and then move on to the historical records of Egypt and Assyria.

The Biblical Mentions of the Philistines

The Bible identifies he Philistines as the descendants of Casluhim (Genesis 10:13–14). According to the biblical genealogy, Casluhim was the son of Mizraim. Mizraim is the father of the Egyptians; his name is Egypt’s name in Hebrew to this day. This makes Casluhim the grandson of Ham and the great-grandson son of Noah. From later biblical accounts we learn that Casluhim and Caphtorim—another son of Mizraim—went and settled in the island of Caphtor, modern-day Crete, which was named after him. This is spelled out in the prophecy of Amos: “‘Are you not like the Ethiopians to me, O people of Israel?’ says the LORD. ‘Did I not bring up Israel from the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor and the Syrians from Kir?’” (Amos 9:7. See also Jeremiah 47:4).

When we examine the biblical text, we find the first use of the term “the Philistines” in the Bible in the book of Genesis—in particular in the narrative of Abraham’s covenant with Abimelech, king of Gerar. In this account we read that the two men “made a covenant at Beer-sheba: then Abimelech rose up, and Phichol the chief captain of his host, and they returned into the land of the Philistines” (Genesis 21:32). In Genesis we find additional references to the Philistines, their land, or their king in the days of Isaac (see Genesis 26:1, 8, 14, 15, 18). Famously in the narrative of the exodus from Egypt, we read that the LORD led the Israelites away from the way of the land of the Philistines (Exodus 13:17). Later in Exodus, the LORD promises to establish the borders of the Israelites from the Red Sea to the sea of the Philistines (that is, the sea by the land where the Philistines lived). Elsewhere in the Bible this sea is called “the Great Sea”—known to us today as the Mediterranean Sea (Exodus 23:31).

You will see later in this article that we do not have any historical records of the Philistines prior to the 12th century BC (that is, centuries after the time of Abraham and Isaac). Therefore, many claim that since the Philistines did not migrate to Canaan until the 12th century BC, then Bible is wrong in referring to them in the days of Abraham and Isaac centuries earlier. This is the conclusion of the hasty and unlearned! A more careful and keen look at the biblical text and the historical evidence shows otherwise.

There are a few different ways we can address this. First, it is quite possible that these early mentions of the Philistines are anachronistic, that is, reworded/edited at a later time in the history of the Israelites using terminology/names that were familiar to the Israelites at the time. Examples of these later edits are plenteous in the Bible. For example, in the account of Esau (centuries before Israel’s first king Saul was crowned) we read, “These are the kings who reigned in the land of Edom, before any king reigned over the Israelites” (Genesis 36:31). At the time Moses wrote Genesis there were no kings reigning over Israel; in fact, Israel was not even a nation yet. Thus this language is clearly anachronistic.

Alternatively, it is also possible that as far back as the time of Abraham and Isaac there were scattered groups of the Philistines living across the land of Canaan. For one, migrations rarely happen over a generation or two (think about immigration from Europe to North America since its discovery and until our modern day). Thus it is possible that the Philistines began their migration eastward at the time of Abraham. Second, we know that some Philistines were fighting in the Egyptian army as mercenaries prior to their mass migration to the coastal plains of Canaan. This suggests that they had moved to Canaan in smaller groups much earlier. Third, we also know that their campaign against Ramses III was via sea and land, which suggests that they had settled by the eastern border of Egypt at an earlier time (see the discussion below).

In support of this view we must notice the textual differences between the Bible’s description of the Philistines at the time of Abraham and Isaac and that at the time of Joshua and the judges onwards. For example, the Bible refers to Abimelech as the “king of the Philistines” (Genesis 26:1, 8). The Philistines at the time of Samson and David had no one king over them. This suggests that at the time of Abraham and Isaac they were a united group. In contrast the later Philistines lived in five different cities, featuring separate city-state governments with no one king reigning over them but were governed by five lords (Joshua 13:3). Second, the Philistines of Abraham and Isaac were generally peaceful seeking to live along side other groups in the land (Genesis 21:22–26). The Philistines of Samson and David were quite violent seeking to control the surrounding territories. Even more importantly, Gerar—the epicenter of the Philistines’ presence at the time of Abraham and Isaac—was not included in the five cities of the later Philistines (see Joshua 13:3). Thus, it is clear that the earlier Philistines were a distinct group from the later one although both groups likely migrated from the eastern Mediterranean westward to Canaan.

After their mention in Genesis at the time of Abraham and Isaac and their brief reference in Exodus, the Bible is devoid of any mention of “the Philistines” until we arrive to the book of Joshua where we read the LORD’s command to Joshua concerning the land that still remained to be conquered calling it the borders (or region) of the Philistines (Joshua 3:12, 13). Starting with the book of Judges onwards the Philistines take a more visible role in the biblical narrative as we read about their continuous conflicts with the Israelites in the days of Samson, David, and the latter prophets.

Now that we have covered their mentions in the Bible, let’s find out what the historical records say about who they were.

Who Were the Philistines?

Historically we know that the Philistines were among the “sea peoples,” that is, the seafaring peoples who came from the islands of Crete and Cyprus. They settled in the five cities of the Philistines in coastal plains of the land of Israel around the time the Israelites entered the promised land. Those five cities were Gaza, Gath, Akron, Ashkelon, and Ashdod. From what we know about the behavior of the Philistines they seemed to be known for dispossessing existing inhabitants of their land and settling in it. The Egyptian records clearly show that this is what they attempted to do to the northern coast of Egypt and the Bible shows that this is what they tried to do later to the Israelites. This is attested to in the Bible as we read in Deuteronomy, “As for the Avvim, who lived in villages as far as Gaza, the Caphtorim, who came from Caphtor, destroyed them and settled in their stead” (Deuteronomy 2:23).

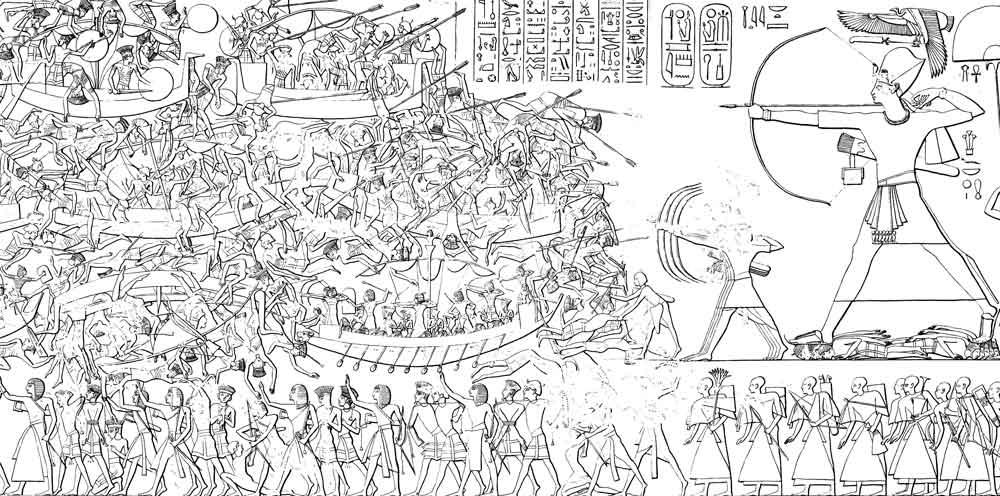

Ramses III defeating the Sea People in the Battle of the Delta, as depicted on the north wall of Medinet Habu, 1200-1150 BC

The first recorded account of the Philistines in the Egyptian records comes to us from the walls of Madinet Habu from the reign of Ramses III. According to these Egyptian records the Philistines attempted to invade Egypt by land and by sea after ravaging Cyprus, Anatolia (western Turkey), and Syria. In the Egyptian historical records they were referred to as prst (or peleset). These prst were defeated and repulsed by the Egyptians around 1191 BC. I should mention that Egypt is not the only civilization in the ancient Near East that left behind a record of the Philistines. The Assyrian records mention them as well, referring to them as Philisti or Palastu.

It is important to note that the Philistines are depicted as Europeans on the monuments of Ramses III. Their pottery also shows connection to the Greek islands in the Mediterranean, particularly Crete. As explained above they were the descendants of Casluhim, the descendant of Ham. In contrast, the Palestinians of our modern day identify themselves as Arabs, descending from the Arabian Peninsula. According to this self-identification and according to their own Islamic narrative, they would be the descendants of Abraham through his son Ishmael. It is indisputable that Abraham comes from the lineage of Shem. This would make the Palestinians the descendants of Shem as well, and not Ham who is the father of the Philistines (see above). The biblical-historical Philistines had no association with the inhabitants of Arabia (modern day Saudi Arabia) who are said to be the ancestors of today’s Arabs (including the Palestinians). The two are completely distinct and separate peoples with no historic or ethnic associations. Thus the Palestinians can either be the descendants of Abraham or the descendants of the biblical Philistines—but they cannot be both.

The Philistines continued to live in the southwestern coast of Israel until the time of the Babylonian exile. They were among the many peoples exiled by Nebuchadnezzar II, king of Babylon. Though Philistia/Philistines are mentioned after the exile by Ezekiel and Zechariah, these mentions strictly refer to the region that had once been inhabited by the Philistines. There is no historical or biblical record of their inhabiting any part of the land of Canaan after their exile to Babylon. From the 5th century BC onward there are no historical or biblical records of the Philistines.

But if all the above is true, then why is the ancient land of Israel called “Palestine” (filisteen in Arabic) to this day? After all, filisteen signifies the land of the Palestinians, doesn’t it? We will discuss these questions and more in the remaining sections of this article.

Where Does the Name Palestine Come from?

Simply put, there is no record of the land of Canaan being called “Palestine” (or filisteen) before AD 135. Though Herodotus uses the term Palaestina in the 5th century BC, he does so referring to the southwestern region of Canaan, historically known as Philistia—the old homeland of the Philistines (see the discussion in Part 1 of this article). Following the revolt of AD 70 and the subsequent destruction of Jerusalem another revolt began in AD 132. That too was crushed three years later in AD 135. To punish the Jews, Emperor Hadrian renamed the land of Israel to Syria-Palaestina, taking after the name of the Jews’ historic archenemy—the Philistines (the word Palaestina signifies Philistine in Latin). In a further effort to eradicate the land’s Jewish identity, he also built a temple to Jupiter on the site where the Jewish temple once stood. This is the same tactic the Arabs used centuries later to confer their Arab identity on the land by building the Dome of the Rock and the Aqsa mosque in the same location. Later the entire land was simply renamed Palaestina. From that point onwards, the name of the land continued to be “Palestine” or filisteen.

So Who Are the Modern-day Palestinians?

There is no historical records of the origins of the Palestinians of today. History is completely devoid of any record of a nation called “Palestine” ever existing whether in the biblical land of Canaan or anywhere else for that matter. There is no record of a Palestinian state in Palestine even during the time in which the land was fully under Arab/Muslim control since the 7th century to the early 20th century. We find no history of ruling monarchy, kings, queens, or presidents of a nation called “Palestine.” The national anthem of “Palestine” was composed in 1965 and formally adopted in 1996. We have no record of a national anthem of “Palestine” prior to that time. The white, green, red, and black Palestinian flag was adopted in 1964. There is no record of it or of any other flag for a “Palestinian nation” before that date.

Invariably, nations who existed over the course of history produced pottery, left behind inhabited or abandoned cities, and can be traced back through literature, language, and the like. We find none of that when it comes to today’s Palestinians. In fact, tracing the origins of today’s Palestinians is much harder than tracing the biblical Philistines who lived centuries ago! This is partly due to the fact that there is never any mention of a “Palestinian state” or a “Palestinian people” in any of the writings of the ancient historians such as Herodotus, Philo, or Josephus.

Some of the Roman historians who wrote about Jesus of Nazareth, such as Tacitus and Suetonius make no mention of a Palestinian state before or during their time. One would expect to find such a mention in any Roman source of the era had such a state existed, particularly that the Romans were not especially fond of the Jews and would have welcomed any opportunity to dispossess them from their ancestral homeland. Motivated by their hatred towards the Jews, the Romans would have been quick to restore the land to its Palestinian owners had such owners ever existed. In fact, the Romans tried to erase the Jewish identity of the land by renaming it “Syria-Palaestina” after Israel’s historic enemy—the Philistines (see above for more details). Had there been such a people called the Palestinians back then, we would have seen the Romans give the land back to them as part of that attempt; but we find no such record. The fact that all historians of that era are silent when it comes to the existence of a Palestinian state shows that there was never one.

In most news outlets and in the recent rewriting of history, we are told that the Jews began living in the land after the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. This is factually and historically untrue. The Jews never ceased to live in the land even after the Arab conquest. After the Arabs defeated the crusaders and despite its increasing Muslim population, Arabs, Christians, and Jews continued to live in the ancient land of Canaan. In 1948 the state of Israel as a political entity was established after it had ceased to exist for nearly two thousand years. However, the Jewish presence in the land never ceased in one form or another.

Did the Arabs Always Live in “Palestine”?

The first mention we find in the history books of Arabs (not Palestinians) in the land of Israel is during the Arab conquest in the 7th century AD. After the split of the Roman Empire in AD 395 the land of Israel was controlled by the Byzantine Empire—the eastern wing of the Roman Empire. Following the emergence of Islam in the Arabian Peninsula in the early 7th century, the Byzantine Empire was subsequently defeated and the land came under Islamic rule in AD 636. In that year most of the land was conquered by the Arabs, with Jerusalem and Caesarea surrendering shortly afterwards in 638 and 640 respectively.

With the construction of the Dome of the Rock in AD 691 and the Aqsa mosque shortly thereafter, began the Arab influx from the Arabian Peninsula to the ancient land of Israel. Gradually the religious and the social identity of the land was transformed from a predominantly Christian land to mostly Muslim. (Recall that in the seven centuries that followed the rise of Christianity the Levant region was a strong Christian epicenter). Heavy taxation (el-jizya in Arabic) was imposed on those Christians who refused to convert to Islam. Those who could not afford to pay this tax had to choose between death or converting to Islam. This oppression is what eventually led to the crusades of the Christian countries in Europe in an attempt to recapture Israel from the Arabs. The crusaders recaptured Israel in AD 1099 and the land came under Christian rule again. This success, however, was short-lived. In AD 1187 Saladin (more properly Salah el-Din el-Ayubbi) dealt a decisive blow to the crusaders and the land came under Arab/Muslim control once more but for a much longer period this time.

A series of successive Muslim empires dominated the land beginning with the Ayyubids to the Mamluks and ending with the Ottoman Empire in 1517. The Ottomans remained in control of the land until it was captured by the British after the Ottomans were defeated in World War I in 1917. At the end of the British Mandate in 1947, the State of Israel was established in May 1948 in the ancient land of Canaan for the first time since its total collapse in 586 B.C. at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon. The brief timeline below shows the sequence of empires that controlled the land of Canaan/Israel up to our modern day. For brevity, I have shown these kingdoms since the Roman Empire onwards. Click here to view an interactive timeline of the kingdoms and empires that controlled the land of Israel since the Canaanite Period.

Why is this brief timeline important? Because in the nearly 1,300 years that the land of “Palestine” was fully under either Arab or Muslim control, we do not find any record of a Palestinian state ever established. Between AD 636 and AD 1917 the land of Israel was controlled by either Arab Muslim or Turkish empires with a brief interruption of less than 200 years beginning in 1099. In fact, after the partitioning of the land in 1947, the modern kingdom of Jordan was given full control over all of the West Bank and the entire city of Jerusalem. This remained so until the Six Day War of 1967. Again, the Jordanians neither established a Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital—as frequently claimed by modern-day Arabs and Muslims alike—nor returned Jerusalem to the Palestinians as its “rightful owners” to claim it as their capital. Interestingly, during that time Jordan was home to nearly all the Palestinians who had fled the land as a result of the 1948 war. But Jordan never helped them return to their “homeland” either in Jerusalem or in the West Bank and establish their own state of Palestine.

It is noteworthy that up until the late 1960s the Arabs living in “Palestine” were called “the Arabs of Palestine.” The term “the Palestinian people” appears officially for the first time in 1968 in the charter of the Palestinian Libration Office (PLO). As evidence of this, the Arabs who were exiled from “Palestine” during the Arab-Israeli 1948 war were not referred to as “Palestinians” or “the Palestinian people” but were rather called “the Arabs of Palestine.” Prior to the 1960s those exiles were also referred to as “the Arabs of 1948.” There is no record of using the term “the Palestinian people” before the establishment of the PLO. In fact, the term “Palestinians” was used to refer to the inhabitants of the land of Israel both Jews and Arabs prior to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. The term gained its distinctively Arab-Muslim connotation after 1948. Nearly without exception, a land gets its name from the name of the people who live in it (at least in the context of the ancient Near East). Canaan was named as such because it was where the Canaanites (the sons of Canaan) resided. Egypt is where the Egyptians live. The land of Israel gets its name from the sons of Israel (the biblical Jacob)—and so on. The Palestinians are the only people (that I know of at least) who were named after the land they claim. As mentioned earlier, the land was called “Syria-Palaestina” thousands of years before the term “Palestinian” or the “Palestinian people” came on the scene. While all nations get their names from their peoples, the Palestinians get their name from the land which they claim to be theirs!

Conclusion

In the end, regardless of your religious or political views I believe that we all should be searching for the truth. After all isn’t that what research is all about? Isn’t true knowledge supposed to be a quest to seek and find truth? While many of us have their biases, my own experience has showed me that there are two different kinds of researchers. The first is one who has an already established conviction in mind and his quest simply aims to find evidence to support that conviction. These “truth seekers” or “advocates” have already reached the conclusion of their quest before they even start it! Under this view, bias trumps truth. The second kind is one who follows the evidence wherever it leads and no matter how uncomfortable the conclusion may be. Even if they start with a notion in mind as to where they would like their search to take them, they still maintain the ability to course-correct if they find compelling evidence to do so. In this case truth trumps bias.

I grew up in Egypt, a predominantly Muslim country with a heavy bias against Israel. However, growing up in a Christian household where I was taught that the word of God trumps everything else, I quickly came to realize that much of what we were told and taught—especially pertaining to the history of “Palestine”—was untrue. Lest you think that every Christian in Egypt holds the same views as me, let me tell you that the late Patriarch of the Coptic Church of Egypt, Shenouda III, as recently as 2002 declared in a public address to a mixed audience of Muslims and Christians that the Palestinian people were the rightful heirs to the land of Israel. In fact, working with the Egyptian authorities, for decades he imposed a ban on Christians from traveling to Israel although both countries have had stable diplomatic relations since the Camp David Accords of 1978. His position represented the official stance of the church of Egypt on this issue. It was not until his death in 2012 that the Christians of Egypt could travel to see the sites where many of the events described in their Bible took place. Still, when it comes to this contentious issue many (if not the majority) of Christians in the Middle East today echo the official narrative of their governments and not of the biblical and historical truth.

In closing I acknowledge that not everyone reading this will agree with me—and that is expected. I equally acknowledge that many will be staring at truth right in front of them and yet refuse to believe it. Though sad, that too is expected. I have written this article to put you as the reader at this fork in the road. Which camp of seekers do you choose to belong to: those who first reach a conclusion and then research to find evidence supporting their conclusion or those who research first and then draw their own conclusion based on the evidence they discovered?